Stop trying to make the NHI happen – fix what we’ve got: expert

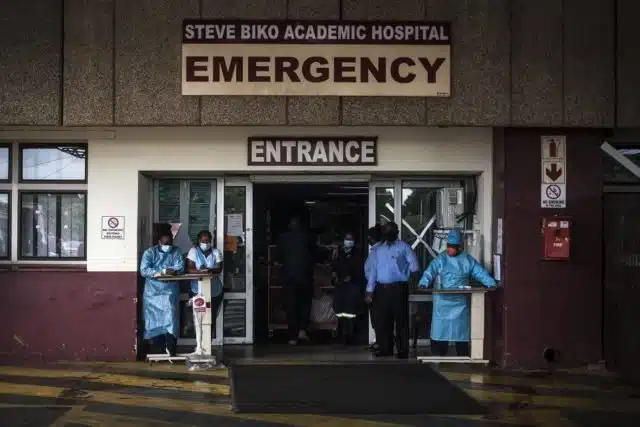

South African think tank, the Centre for Risk Analysis (CRA) hosted a discussion this week about the viability of the government’s National Health Insurance scheme, which it says is moving full steam ahead, despite concerns raised by stakeholders in the private and public healthcare space.

Deputy director general at the Department of Health, Dr Nicholas Crisp, told the Sunday Times this past week that both the public and private healthcare sectors in South Africa are in a poor state, adding that “one just looks prettier than the other”.

Crisp said that the country has two parallel healthcare systems, and the NHI was a project to tie these two systems together in a “massive, multiyear reform programme for the health system going forward”.

He said that the country spends 8.5% of its budget on healthcare and has the 35th biggest economy in the world – but it has poor health outcomes. He said that this was even worse because the country had two healthcare systems which are both not functioning well.

Speaking to the CRA, Michael Settas, managing director of health insurer, Cinagi, and head of the health policy unit at the Free Market Foundation, said that trying to paint the private and public sectors as ‘equally as bad’ is a poor attempt by Crisp to justify why the NHI should exist.

“The private sector has problems, there’s no question about it. But we’ve had the six-year-long healthcare market inquiry…and it came up with a blueprint on how to fix it. It’s regrettable now that blueprint has been shelved to be replaced by NHI – which is largely ideologically driven,” he said.

Settas noted that there has been very little in the way of technical feasibility done for the NHI, and to date, there has still not been any costing done. At its core, the NHI simply wants to nationalise the private sector and amalgamate it into the public, Settas said.

The CRA posed the question that if the NHI had access to all the money resources from the public sector – especially medical aids – would it be able to fix the problems in the public sector?

Settas said that throwing money at the problem isn’t a solution because the fundamentals of public healthcare are broken. “The political answer to anything is ‘more money’,” he said.

“It fundamentally ignores that the public sector health budget from 2000 to 2020 doubled – in real terms and per capita terms. That’s an enormous increase in resources. So if the argument is that it’s a resource issue, then why aren’t the public sector outcomes better than they are?”

“All we see every day is a decline. There’s always a publication somewhere with some story about a failure in the public sector. It’s becoming so obvious that it can’t be ignored. To argue that it’s a resource problem is complete nonsense,” Settas said.

The same can be said about personnel, he said. A review published in 2020 showed that the number of medical personnel employed by the state was 50% higher than in 2006.

“That’s a massive increase in human resources as well. We should be getting better health outcomes. The trend should be upwards, improving, because of the massive increase in resources. But we’re not seeing this.”

Settas said that the problems in South Africa’s healthcare sector – particularly the public sector – are about failed fundamentals.

“There’s just a complete lack of governance. The frameworks have either been dismantled or removed, and there’s simply no management or accountability within the department (of health), which has led to things like widespread moonlighting by medical personnel,” he said.

Settas cited a Wits University study from 2014 that showed that two-thirds of nurses in South Africa reported overtime and moonlighting activities, which posed a risk to patient care.

“The NHI is not going to fix those things. You can throw more money at a dysfunctional system, it’s not going to fix it. You have to fix the fundamentals – the management and those sorts of issues. If you can fix that, then you don’t need an NHI, you fix what you’ve got.”

“People don’t realise that South Africa’s public sector is a very substantial asset – by far the biggest public health system on the African continent. By miles. We should be doing much better. There I agree with (Crisp). But I don’t agree that the NHI is the way to go.”

Settas said that building healthcare systems takes decades and that the NHI is more a political tool being used by the government in between election windows. He also said that talk should move away from ‘building’ a new healthcare system in the country because South Africa doesn’t need to do this – it already has one.

“(The NHI is) all about selling a political aspect – but we don’t need to sell it. What (the government) should be selling is that we have a very substantial public health system that’s got lots of problems, but the asset is still there, we haven’t lost that.

“Let’s fix that, we’ll have a lot more success than trying to build this ‘new system’ which, even if they could build it – and I don’t think they can – will be decades away.”

Read: Here’s how private medical aids could work with the new NHI in South Africa